Madison School And The Self-Support Principle

The idea to start such a school belonged first to David Paulson who, in 1901, encouraged Sutherland “establish a school whose doors would swing open to any young man or woman of worthy character who is willing to work for his expenses. I would never turn away anyone who had the love of education and the courage to work for it. You ought to have a large tract of land and provide facilities for student self-support” (Madison Survey, 9 May 1934).” The Self-support principle had to be a key element for the functioning and the development of the school, following the model of the biblical schools of the prophets.

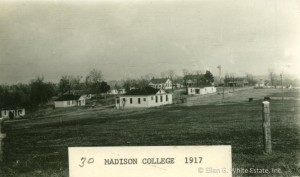

Madison sought to educate the whole person: the body, mind, and spirit. The basic operating principle was that of self-support, but above this Madison most effectively instilled in its students and teachers a spirit of self-sacrifice, service, and love of a simple frugal life close to God and nature. Any qualified student, no matter how poor, was able to receive an education at Madison as long as he or she was willing to work each day at the school to earn expenses. Under the Madison work-study plan, every student had to work for at least half (and preferably all) of his or her expenses. There was no set tuition in the early years and two-thirds of the students entered with only the required small deposit. The early years were trying: years of faith, hard work, and frugality. Faculty salaries were meager. Students and faculty worked together for 5 hours each day. Until the 1930s they ate only two meals a day. Over the years, they built all the school’s buildings with their own hands. In 1939 Ripley’s Believe It or Not called Madison “the only self-supporting college in America.” That same year Dr. Philander P. Claxton, US Commissioner of Education, praised Madison saying: “I have seen many schools of all grades in many countries, but none more interesting than this. Nowhere else have I seen so much accomplished with so little money.”

Other “ingredients” of Madison’s success

Madison in its early years was a special school. As shown by its name, Nashville Agricultural Normal Institute, it offered training in agriculture, which Mrs. White believed should be basic to all other studies, and in “normal” courses, or teaching. Thus its purpose was to train self-supporting, domestic and foreign missionary teachers and workers. The primary entrance requirements were a mature mind and an intense interest in self-supporting missionary service. Unlike other schools, for example, Madison had no organized athletic program. There was no time for such things, and students got plenty of exercise through farming and useful work. Sutherland had inaugurated this concept when, as president of Battle Creek College, he had plowed up the athletic field to make a vegetable garden.

After it got underway, Madison lost no time putting into action its plan of sending teachers to set up Madison-type “rural units” or “hill schools” to help the impoverished people of the South’s hill and mountain country who had no schools. By 1914 some 40 such schools, started from Madison, were in operation in the South with more than 1,000 students in attendance.

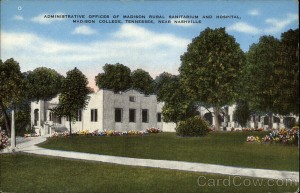

Both Ellen White and Sutherland believed strongly that schools should be located in the countryside, and that they should support themselves through farming and other activities that provided education and income for the students, and service to the surrounding community. Two such activities were the operation of a sanitarium (hospital) and a small plant to produce healthful natural foods. Madison was the first Adventist school to have its own sanitarium, which started in about 1906.

The school also had its own printing business (The Rural School Press) and publishing house. In 1919 the weekly school newspaper, The Madison Survey, began publication. With a monthly circulation that eventually reached 21,000, it was sent out free of charge as the voice of the college to friends, alumni, and other Adventist groups. By 1938 Madison had 27 student-run campus industries.

More details about this remarkable Madison School you can read in the book Madison – God’s Beautiful Farm, written by Ira Gish and Harry Christman (you can read it partially from the link provided).

The beginnings of the Madison Missionary School. (click to read the article)